As was recounted in previous posts in this series, the societies about to embark on the Great War, in 1914, were enthralled by a comprehensive set of delusions regarding the nature of that war and the course it would take. Famously, it was believed in the capitals of the principal belligerents that the war, begun in August 1914, would be over “before the leaves fell”—that the soldiers sent to fight that war would be “home by Christmas.” It was only in the context of those delusions that is it unsurprising to see literally hundreds of pre-war and early-war postcards portraying the conflict as a game, or as “child’s play”—many such cards in fact featuring children, often in uniform.

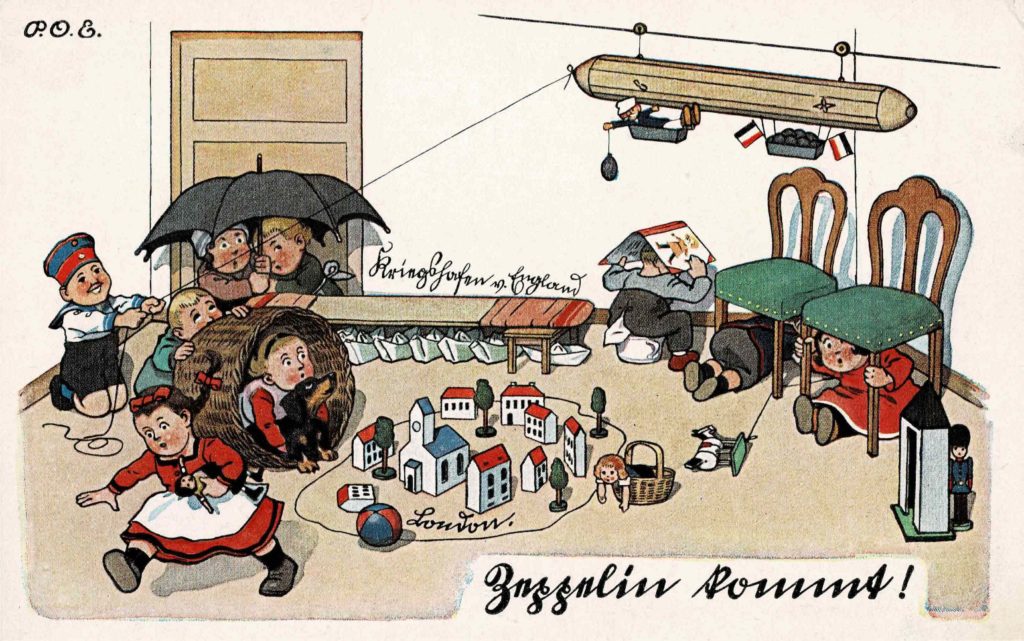

The German postcard reproduced above (“Zeppelin Coming”)—posted seven months into the four-year war—certainly stands as an exemplar of the naïve war-as-game and war-as child’s-play genres popular during early war days; but it is also, from a historical standpoint, much more. The postcard’s image and references not only evoke a sense of the Great War that is at odds with its coming reality, it provides a foreshadowing of humanity’s future that is the more chilling for the lighthearted purport of that imagery.

In the pictured “game,” only one child is in uniform. The smiling German child-soldier on the card’s far left is manipulating, by string, a toy dirigible that is dropping little bombs on a cluster of buildings captioned “London.” The card’s other children—hied from “London” and cowering from the dirigible’s attack—are in civilian dress.

The concept of “total war” has been attributed to Carl Phillipp von Clauswitz (1780-1831), the Prussian general and military theorist. He never used the term, however, and the closest he came to the more modern concept was his acknowledgment that the notion of waging war in a limited way is a “logical fantasy” . . . that logic and natural competitive impulses would always impel belligerents to use all means at their disposal to achieve victory.

It cannot be said that the Germans, in their 1914 invasion of Belgium, were the first nation to employ the systematic execution of civilians to demoralize and defeat an enemy in war. There is no dispute, however, that the Germans, in the Great War, were the first to employ a terror tactic of particularly far-reaching consequence: the bombing of civilian populations from the air.

A German general, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, first conceived and developed rigid dirigibles, which became widely known as “zeppelins.” In the very first month of the war, Germany dropped bombs from a zeppelin on the Belgian city of Liège, killing nine civilians. In August and September of 1914, German zeppelins and propeller aircraft conducted a number of bombing raids on Antwerp and Paris.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most concerted air campaign was reserved by Germany for England—Germany’s most hated enemy. The initial proposal was originated by the German Admiralty, whose chief, Alfred von Tirpitz, made the campaign’s objectives perfectly plain:

The measure of the success will lie not only with the injury which may be caused to the enemy, but also in the significant effect it will have in diminishing the enemy’s determination to prosecute the war.

Germany’s first successful zeppelin raid on England was conducted on January 19-20, 1915. That raid resulted in the deaths of four civilians in villages in the south of the country. The first successful zeppelin attack on London was in May of 1915. Germany conducted twenty raids in 1915, killing 181 people and injuring 455.

The raids continued into the following years of the war, targeting, in particular, the East End of London. On June 13, 1917, a formation of Gotha biplanes bombed London’s Poplar District. One bomb fell on that area’s Council school, killing eighteen students in that school’s infant class—sixteen of whom were between 4 and 6 years old.

Over the course of the war, German zeppelins (referred to as “baby killers” by Britons) staged more than 50 attacks on Britain, resulting in approximately six hundred civilian fatalities (and another two thousand casualties). Those raids had no material impact on the outcome of the war. They did, however, establish a precedent.

The report of Great Britain’s formal inquiry into the country’s ability to defend against air attacks led to the creation of the Royal Air Force, on April 1, 1918. Although Germany expanded the scope of its bombing of civilian targets in the Second World War (Warsaw, Rotterdam, and Coventry being added to London as blitz targets), Britain and its allies had gone to school in the intervening years, and put to their own use Germany’s war-making innovation. Echoing with eerie exactitude Germany’s stated objectives in bombing British civilian targets in 1915, Sir Arthur (“Bomber”) Harris, Commander-in-Chief of the RAF’s Bomber Command during the later years of World War II, stated as follows in justifying the objectives of Britain’s bombing of German cities in 1942, 1943, 1944, and 1945:

[T]he aim of the Combined Bomber Offensive . . . should be unambiguously stated [as] the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers, and the disruption of civilised life throughout Germany. . . . [T]he breakdown of morale both at home and at the battle fronts, by fear of extended and intensified bombing, are accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy. They are not by-products of attempts to hit factories.

Putting aside the nuclear attacks on Japan, six of the ten most devastating bombing campaigns of World War II were sustained by German cities—Kassel; Darmstadt; Pforzheim; Berlin; Dresden; and Hamburg. It is estimated that Germany incurred between 350,000 – 400,000 civilian deaths in those attacks (including more than 40,000 in Hamburg, and as many as 50,000 in Berlin).

Arthur Harris’s most famous statement made reference to a biblical prophecy (Hosea 8:7), as follows:

The Nazis entered this war under the rather childish delusion that they were going to bomb everybody else, and nobody was going to bomb them. . . . They sowed the wind, and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.

Harris made reference to Germany’s bombing of specific cities (including London) in the war then ongoing, no doubt considering it unnecessary to invoke earlier precedents. But, had he wanted to invoke such precedents, he could have. The 1915 postcard above, to the point, shows a member of Germany’s military, smiling . . . and sowing the wind.