~ [sign me] Frequent Visitor

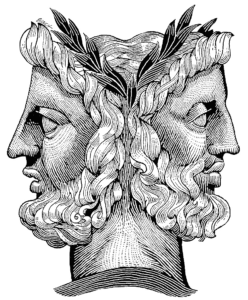

Is there any one of us unfamiliar with the trenchant bits of wisdom that begin, “There are two kinds of people…”? Among the more familiar pearls from that string:

There are two kinds of people: those who see

the glass as being half empty, and those

who see it as being half full.There are two kinds of people: those who do

the work, and those who take the credit.

And etc.

The humorist, Robert Benchley, lampooned the multiplicity of efforts to express profound truths in that formulaic way, writing: “There are two kinds of people in the world, those who believe that there are two kinds of people, and those who do not.”

The foregoing having been said, I am abashed to admit that I have been afforded an insight (or what I take to be one) that expresses itself in that same hackneyed form. Specifically, it occurs to me that there are (yes!) two kinds of people: those who are attracted to speculations concerning the future, and those more interested in the events and inhabitants of the past.

I am a person of the second type. Although I admit to having been transported by the poetic conjurings of Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, I watched but a few episodes of “Star Trek,” and viewed only two of the “Star Wars” films. In contrast, I have formed collections of the ephemera of past societies, and am drawn always to biographies of figures who loomed large in their times . . . meaning, times past. So powerful, to me, is the attraction of the past that I devoted the past several years to study of the First World War—and have in fact fashioned my insights into that war, and those times, into a book manuscript (just completed, and now in search of a publisher).

While I cannot speak to the appeal of the speculative future, given that I am a person of the other kind, I believe that I can account for my interest in the past. I believe that I am drawn to it because it was populated, not with speculative beings (however richly imagined), but personages of flesh-and-blood—real people. The things they said and did are for that reason more relatable to me because of their actuality (even if those utterances and deeds must now be spoken of in the past tense).

My recent study of World War I will provide an example of what moves me. When pressed by the mighty German Empire, in 1914, for leave to traverse Belgium in order to prosecute Germany’s planned attack on France, Albert I, King of the Belgians—fully appreciating the consequences—memorably refused that demand: “Belgium is a country,” King Albert told the Germans, “not a road.” A real person spoke those words of defiance, and stood with his people as they paid a real price. The actuality of it—the fact that a real man took a heroic stance in the face of a real threat—gives that moment weight that the speculative future, for me, can never amass.

And, of course, tracing the Great War to its aftermath of rancor and revanchism helps to explain why six million of my co-religionists were (among those of other tribes, faiths and affiliations) systematically murdered, by real monsters, in real ways. It is one of the horrors of the past; and I find it incumbent upon me to know about it so that I can help to keep it there.

In sum, in the contest between speculations touching on the future and serious contemplations of the past—give me the past.

But of course the exercise of “choosing” is entirely academic. There is no need for action of any kind on the part of anyone, because the past—for better and worse—already has been given to us.

Really.