Stephen Dvorkin

I will not live long enough to see any particular lump of coal become a diamond. But I have lived long enough to see a love song written by one of my contemporaries mischaracterized as “traditional”—the song being thereby attributed to that prolific genius of yore, Anonymous. Such attribution cuts the song loose from the mortal coils of “authorship,” and “copyright,” acknowledging that it has ascended to a stratum beyond names and dates. . . the realm of the Sublime.

But we outrace ourselves. Let us begin at a time when the song in question was still associated with a living man, and made reference to the experiences of a single life, the affections of a single heart.

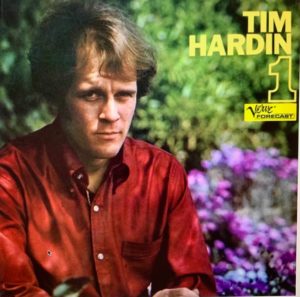

“The Lady Came from Baltimore,” was written by Tim Hardin in 1967. It begins:

The lady came from Baltimore

All she wore was lace

She, wealthy (“all she wore was lace”), and innocent; he, from the other side of the tracks:

She didn’t know that I was poor

She never saw my face

As a subsequent verse makes clear, the observation that the lady never saw the speaker’s face is metaphorical . . . a statement of her inability (the product of her innocent goodness) to see his true nature.

The lady’s name was Susan Moore

Her daddy read the law

She didn’t know that I was poor

Lived outside the law

Susan did not appreciate that the man recounting events had appeared in her life with malign intent:

The house she lived in had a wall

To keep the robbers out

She never stopped to think at all

That’s what I’m about

Susan’s father, a man with experience of the world, did see the man’s face:

Her daddy said I was a thief

And didn’t marry her for love

But in a turn that did not square with his experience, and confounded his expectations, Susan’s father was wrong:

But I was Susan’s true belief

I married her for love

The speaker’s own surprise at that turn of events is summed-up in the song’s chorus:

I was sent to steal her money

To take her rings and run

But I fell in love with the lady

Got away with none

True-love-forsaken is a venerable folk song genre. There are surely other rogue-redeemed-by-love songs; but they are, just as surely, greatly outnumbered. Here, then, is a rara avis: a folk song in which a cynical rogue, bent on mischief, is won to the purity of love by his intended victim’s goodness, her “true belief.”

The compact jewel that is Hardin’s song is rendered in spare poetry and set to a melody that could not better suit its story. Small wonder that other singers wanted to make the song their own. It has been covered, in the five decades since it was written, by Bobby Darin, Joan Baez, Cliff Richard, Ronnie Hawkins, Rick Nelson, and Johnny Cash, among others.

Because of its simplicity it is easy to overlook the song’s subtle sophistication. For example, Susan’s father is not just described as a lawyer: rather, he “read the law.” That term has meaning in the legal profession, and Hardin obviously knew it. Aspiring lawyers “read the law” as a form of apprenticeship. Of course, Susan’s father is presented to us as a man made cynical by experience (not as an apprentice). The passage can be read as referring to the manner in which Susan’s father came to be a lawyer; and the words, in that sense, plainly “scan.” Ultimately, however, any reservation concerning the manner in which Mr. Moore’s background is described is a pointless quibble.

After describing the precaution that was taken to protect Susan’s innocence—“to keep the robbers out”—the speaker notes that “[s]he never stopped to think at all [t]hat’s what I’m about.” In that last phrase, “about,” as a preposition, can be taken in two senses recognized by Merriam Webster: as a description of the speaker’s character (what he was “fundamentally concerned with or directed toward”), or what he was up to (or “engaged in”). Both work in the broad context of the song, and the phrase can be viewed as a double entendre.

In sum, beneath the surface of the song that presents with such simplicity there is real craftsmanship. Early in the 1960s, no less a judge than Bob Dylan pronounced Hardin the country’s “greatest living songwriter.”

Like a number of Hardin’s songs, “The Lady Came from Baltimore” was broadly autobiographical. Hardin met his Susan in 1965. Her name was Morss, not Moore. Her father, a prosecutor and later a judge, did (in the broad sense) “read the law.” In 1969, Hardin released an album titled, “Suite for Susan Moore and Damion” (the latter being the son of Hardin and Susan). Can there be any doubt that the album was created “for love”?

But, in its later innings, Hardin’s relationship with his Susan was not the idyll his song conjured. What cost Hardin that relationship, his musical career, and, ultimately, his life, was his addiction to drugs, which began when he was just sixteen. “First time I got off on smack,” he recalled in an interview, “I said . . . ‘Why can’t I feel like this all the time?’ So I proceeded to feel like that all the time.”

Like other artists (particularly, other artists with drug addictions), Hardin was not of this world. Impelled by the need to support his habit, he was on the wrong side of several financial transactions (including transactions involving the rights to his own his music), which left him increasingly embittered. (It is a sad irony that Susan left Hardin while he was laying down the tracks of what would be the “Suite for Susan Moore.”)

Hardin has been described as a “true romantic”; and, like other romantics of his stripe, he was frequently disappointed that people were not better than they are. He resolved his disillusionment with the world by facilitating an early exit. Tim Hardin died of an accidental heroin overdose at the age of thirty-nine.

As suggested above, Hardin is remembered as a writer of “folk songs.” In what is perhaps the largest category of folk songs, archetypal figures play out stories that are forever repeating, experiencing passions that have been—and will be—experienced universally. A characteristic of the best of the breed is the quality of timelessness.

The cruel war is raging and Johnny has to fight

I want to be with him from morning to night . . .

Which war?

Does it matter?

In the folk song canon generally it does not.

On occasion, a modern master composes a song that captures “folk” qualities: Ian Tyson’s “Four Strong Winds,” Bob Dylan’s “Boots of Spanish Leather,” and John Jacob Niles’s “Go ‘Way From My Window,” for examples. But the great majority of songs making up the folk music canon have been brought down through the generations by oral transmission, their composers unknown. Such songs will be labeled “traditional,” and attributed to “Anonymous.”

The foregoing paragraphs are germane here only because I encountered the lyrics of “The Lady Came from Baltimore” posted on an internet website, characterized as “Traditional?” [sic], without attribution of authorship. Not knowing better, the poster implicitly felt that the song recounted a story that was primal, and timeless, and thus had to have been passed along to us across the generations. I, too, see those qualities, and understand the poster’s mistake.

Unlike the years and pressures that are required to transform a lump of coal into a diamond, “The Lady Came from Baltimore” was delivered to the world, in 1967, as a fully-formed miracle of concision, shining from the first as the gem it will forever be.

How does a song come to be characterized as “traditional”? Perhaps the mischaracterization referred to above suggests that this mysterious process, as regards “The Lady Came from Baltimore,” already is under way . . . that the song is even now losing connection with the man known as “Tim Hardin,” and his time, and, like the other works of Anonymous, will ultimately belong to the ages.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmJVy4yxP34