Propaganda Postcards and the German Invasion of Belgium

“The first casualty when war comes is truth,” observed United States Senator Hiram Johnson in a 1918 speech. Coincidentally, his subject was the Great War—America’s involvement in which Johnson had opposed. “Truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies,” Winston Churchill would candidly acknowledge—but only at a later time, in the course of a later war.

Propaganda, disinformation, and censorship were more extensively and systematically employed in the Great War than in any previous war . . . and those techniques were not the preserve of any single combatant. Germany, however, had unique propaganda needs arising out of the fact that her armies were occupying large swathes of the territory of other European nations (Belgium, France, and western Russia) within the first months of the war . . . a fact which Germany was at pains to justify to the populations of neutral nations—and to important constituencies within Germany, itself.

Giving greater urgency to Germany’s propaganda needs were the circumstances under which the first of those occupations was accomplished. Germany had for years planned to invade and conquer France by moving her armies through neutral Belgium: indeed, her foreign policy during the pre-war years has been viewed as Germany’s orchestration of a pretext to put that plan into action—which finally occurred when German troops launched an assault on the Belgium fortress city of Liège on August 4, 1914.

For a period of years prior to Germany’s invasion of Belgium theorists identified with the Empire’s influential ultra-nationalist parties propounded the position that it was Germany’s destiny to rule over nations occupied by “lesser races.” Indeed, it was the position of political philosophers of that stripe that conquered nations would be better off under regimes based on superior German kultur. Although the books advancing such views of Germany’s destiny were written by Germans, for consumption by Germans, no effort was made to keep the ambitions of German nationalists from the populations of those other nations.

Significantly, the ultra-nationalists’ view of Germany’s larger destiny found its way into the thinking of the Empire’s Kaiser Wilhelm II:

It is my unspeakable conviction that the country to which God gave Luther, Goethe, Bach, Wagner, Bismarck and my grandfather will yet be called upon to fulfill great tasks for the benefit of mankind.

Although the quoted statement does not make express the view that Germany would confer benefits on neighboring countries by conquering and occupying them, that corollary is reflected in Wilhelm’s intimate (if irresolute) involvement in the development of Germany’s war plans. (Indeed, although he grounded the request in the purported need to preempt an attack on Germany from France, Wilhelm had asked Belgium’s King Albert for the latter’s consent to “temporary” occupation of Belgium by the German Army.)

It was against the backdrop of these nationalistic stirrings and conceits that a German publisher could print the postcard below, showing a Belgian girl welcoming an arriving contingent of German soldiers. Implicitly subsumed is the understanding that the Germans are bringing—along with their flags and weapons—superior German kultur. Why, in that circumstance, wouldn’t this girl—and all Belgians—be happy to see the Germans arriving? Indeed, other Belgians should follow this girl’s example (the card suggests) and greet the German Army’s arrival with the white flag the girl is seen to be waving.

The fanciful notion that other nations would welcome the armed imposition of German kultur was quickly laid to rest—a process accelerated by the German Army, and its conduct of the invasion of Belgium. German military leaders felt aggrieved that the outnumbered Belgian Army had the temerity to resist the invasion, thereby jeopardizing the German timetable for reaching the French frontier. Fatefully, the Germans made the Belgians pay for their resistance by systematically executing civilians—men, women, and children—in each town and city that fell before their army’s advance. Six thousand civilian executions were documented, and another 17,000 Belgian civilians died in prison, or as a consequence of forced deportation. Belgian towns and cities, once subdued, were put to the torch.

The Kaiser’s government was surprised by the world’s reaction to German atrocities in Belgium, and undertook to counter international outrage with a propaganda campaign that included the “manifesto” of ninety-three German intellectuals (which blamed the hardships sustained by the Belgians on the Belgians). However, a number of foreign diplomats and journalists had been present in Belgium during the German invasion, personally witnessed German atrocities against Belgian civilians, and reported their observations in the newspapers, magazines, and lecture halls of their native countries. The German propaganda prepared for export thus amounted to an effort to persuade citizens of other nations to reject the eye-witness accounts of respected native statesmen and journalists—and enjoyed the predictable measure of success.

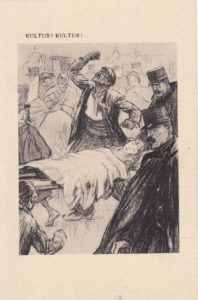

Among those present to witness the invasion of Belgium was an editorial cartoonist for a newspaper in neutral Holland, Louis Raemaekers. Raemaekers, horrified, thereafter used his pencils to make himself the scourge of Germany and its Kaiser. After the German government put a bounty of 12,000 guilders on his life, Raemaekers relocated to London. As a guest of that city’s Explorers’ Club, the normally reticent Raemaekers told the Club’s members, “I, too, have been an explorer, Gentlemen. I have explored a hell, and it was a terror unspeakable.” He was speaking, of course, of Belgium.

The Raemaekers postcard, above, portrays a Belgian man standing beside a litter carrying the body of a young girl (his daughter?). “Kultur!” he cries to the Heavens. “Kultur!” The word, in his mouth, is an expletive.

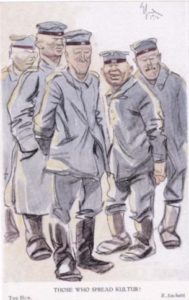

Italy, later to join the Allies, was neutral at the time of Germany’s invasion of Belgium. His country’s neutrality did not prevent Italian editorial cartoonist, Enrico Sacchetti, from creating a series of drawings he entitled, “The Hun.” The postcard below is from that series, and is captioned (in its later British edition), “Those Who Spread Kultur.” In the event the point had not been adequately made, the card’s reverse identifies the caricatured German soldiers as “a group of civilizers in Belgium.”

The Raemaekers and Sacchetti postcards are two representative responses to the German position that German kultur would be a beneficence to those nations upon which it was imposed.

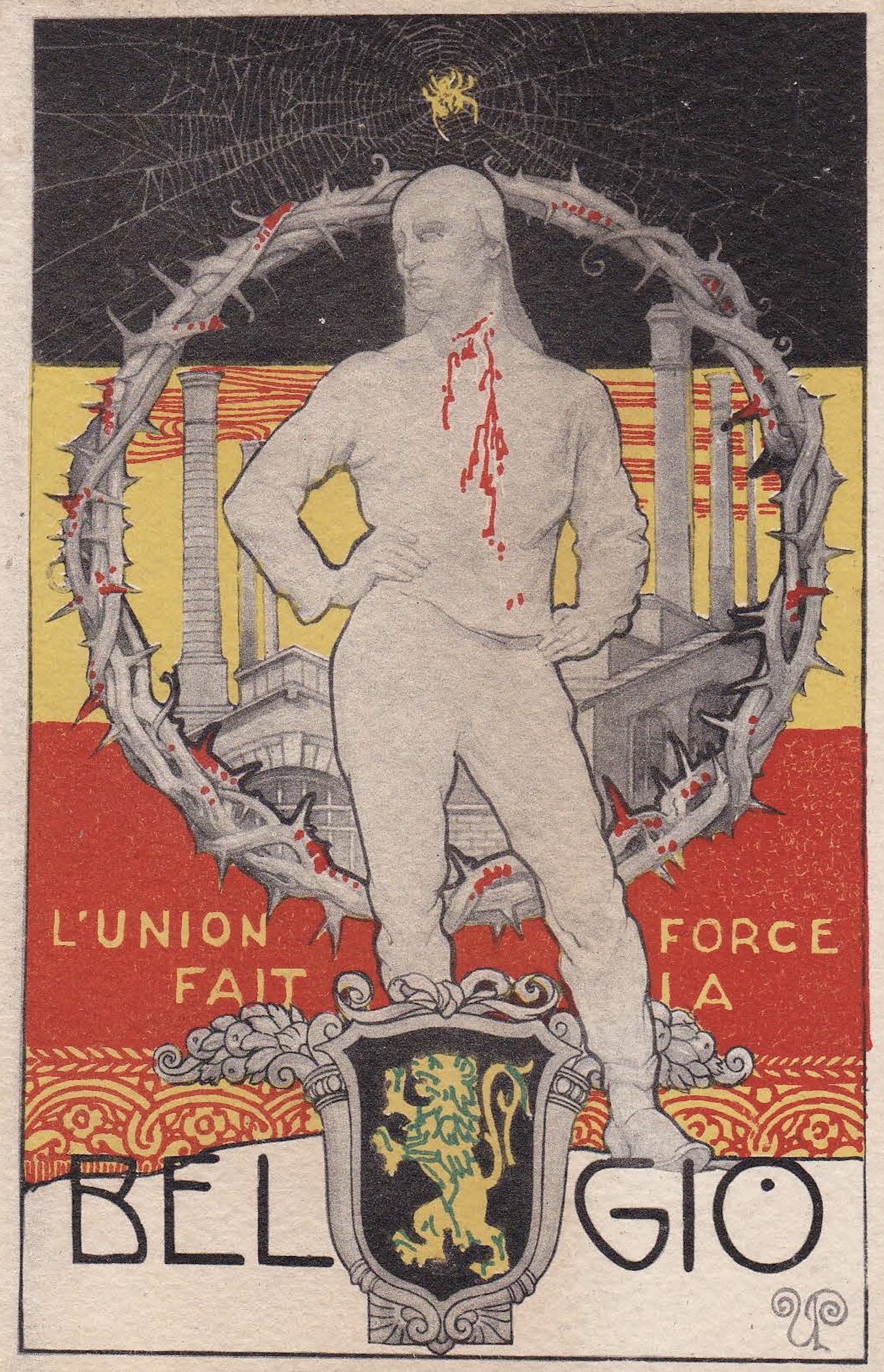

In sum, Germany’s propaganda efforts to justify her invasions of other nations, generally—and of Belgium, specifically—failed spectacularly. The measure of Germany’s failure to escape responsibility for atrocities committed during the invasion of Belgium is encapsulated on the Italian postcard that appears at the top of this piece, portraying the personification of “Belgium,” bloodied, against a crown of thorns. As that book’s editor wrote, in his introduction to a published collection of Raemaekers’ war cartoons, “Belgium made intensely clear to the people [fighting Germany] the single issue upon which the war is joined.”

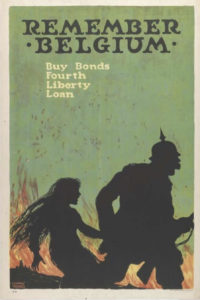

The United States, long neutral, finally entered the war against Germany more than two years after hostilities began. A famous poster designed to inspire Americans to buy bonds to support the war effort appears immediately below.

The persistence of images of atrocities committed in the invasion of Belgium is the measure of the failure of German propaganda to relieve Germany of the villain’s role in the piece. Thus, when an American propaganda artist was casting about for a straightforward image that would bestir Americans to make sacrifices in support of the war effort, he could do no better than to conjure events that had occurred two years earlier, and four thousand miles away. Even there, even still, it was Belgium.