The images on picture postcards sent to and from soldiers on the First World War’s western front captured, in “real time,” the passions and prejudices (etc.) of the men who fought the war, and of the societies that sent them into the trenches. The postcards were rolled off the presses quickly, to serve needs of the moment, and are appropriately viewed as the “social medium” of those times. Soldiers at the front and their loved ones behind the lines did not exchange emails, tweets, or Instagrams: they exchanged postcards—millions of them.

It is striking to see how the cards, as a body, reflected the belligerent societies’ attitudes toward the conflict as it was gathering, and as it was fought . . . showing the changes in those attitudes as the first year of conflict lurched its bloody way into its second; and then its third; and then its fourth. Attention to card images permits us, today, to apprehend a multiplicity of stories within the war’s central story . . . many of which did not find their way into history books.

I undertook to organize hundreds of Great War postcards in such a way that images and events (attitudes, etc.) were mutually illuminated. The project ultimately formed itself into the manuscript of what will hopefully become a book.

The sweeping themes explored in my 600-page manuscript cannot be turned into blog posts in any practical way. But self-contained insights can be teased from individual postcard images that are, to my way of thinking, interesting and enlightening in their own right. It is my intention to present a number of those on JudgmenstHere.

One of the startling facts about the Great War is that, broadly speaking, the societies of its principal belligerents literally welcomed the war’s arrival. That attitude was nowhere more memorably expressed than in a 1914 poem by a young English army officer, Rupert Brooke:

Now, God be thanked Who matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping . . .

In the same poem, Brooke likened the plunge of a generation’s youth into the war to “swimmers into cleanness leaping.”

Thousands of postcard images dating to the early-war period attest to the breathtaking innocence of European societies when hostilities began, making all the more poignant the four-year process of disillusionment that was to follow . . . a process which millions of Brooke’s “swimmers” would not survive. (In a grimly ironic twist on Brooke’s poetic image of the war’s combatants “into cleanness leaping,” thousands of soldiers drowned—and disappeared—in the mud of the infamous Flanders battlefields.)

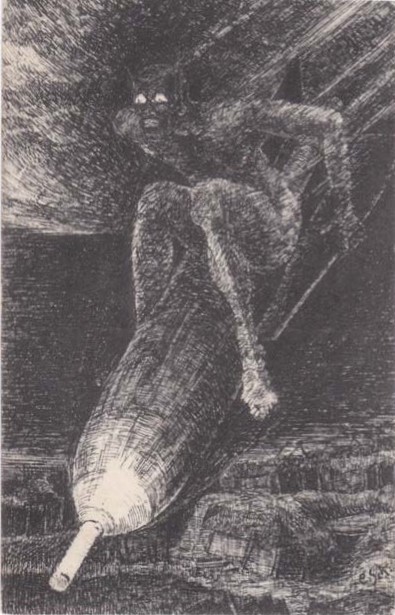

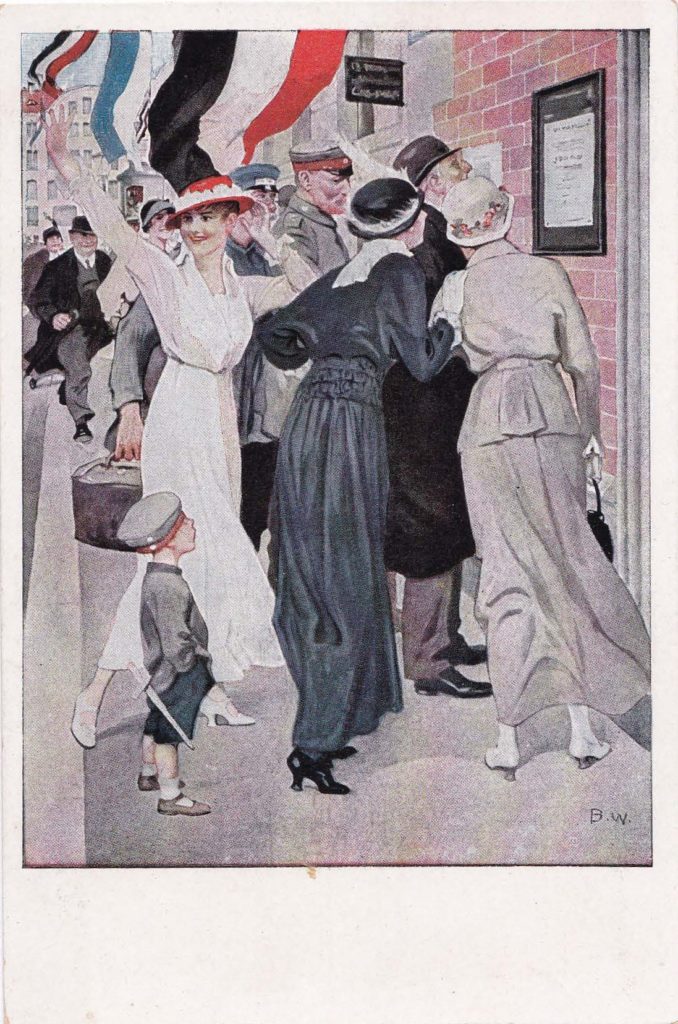

The postcard image reproduced below, and my caption (recited verbatim), serve as the gateway to my manuscript’s consideration of the various delusions under which the belligerent societies were operating in the war’s early months, and the postcard images that reflected (and now memorialize) those delusions.

A Gathering of the Innocent

The societies embarking on the Great War were operating under a set of illusions so comprehensive as to obscure in clouds of romance the less happy realities that would confront them all too soon.

The early-war German postcard reproduced above is a paradigm of the illusions that enthralled entire societies. The card’s image shows citizens of a German town jubilantly studying a board upon which has been posted good news regarding the nation’s war effort. The upbeat tone of the image moreover suggests that the future is bound to provide the Germans with additional opportunities for such festive gatherings: news from the front will continue to be posted—and it will always be good.

Hey Steve, now I have some more time to engage in other subjects. This is just a quick thought.

I understand how general public had free access to postcards of any choice available but what about soldiers. Their choices were limited surely.

So the flow must have been much stronger from the public to the front in quantity and variety.

Is there any record or way to find out more about it. Can you see a postcard salesman sloshing through the trenches, calling out, “ Post cards, envelops, paper, pencils, ….”

Hey Steve, now I have some more time to engage in other subjects. This is just a quick thought.

I understand how general public had free access to postcards of any choice available but what about soldiers. Their choices were limited surely.

So the flow must have been much stronger from the public to the front in quantity and variety.

Is there any record or way to find out more about it. Can you see a postcard salesman sloshing through the trenches, calling out, “ Post cards, envelops, paper, pencils, ….”

Greetings, Sinisa . . .

The men cycled through periods in the trenches, in support trenches, and in “rear areas” further removed from the fighting. It was in those last locations that soldiers purchased cards and other writing materials. One unique type of postcard was ONLY available for purchase by soldiers on the Continent: embroidered silk cards made by Belgian and French civilian women for sale to soldiers on relief from trench duty. Those were regarded as special treasures when received by the folks back home.

The British did have a rudimentary form of postcard, the “Field Service Postcard” (known as the “Quick-Firer”) that could be sent from the trenches: its simple (pre-printed) message was conveyed by striking-out the statements that did not apply. (If anything was added to the Field Service Postcard by a soldier, it was simply destroyed.)

ALL printed postcards were subject to scrutiny by “the authorities.” There was concern about morale in the trenches, and on the “home front.” Of course, outbound correspondence from enlisted men in the trenches was actually reviewed and censored by officers. Correspondence from home, to serving soldiers, generally was not subjected to that sort of review.